Taken from here

Why Parallelism?

- A parallel computer is a collection of compute modules which work together to perform a task efficiently

- In principle, more processors means more power

- However, a major bottleneck is communication speed

- Think of a room of people working together on a calculation. Information needs to travel between them for them to cooperate efficiently. Better communication == faster results

- If communication takes longer than the task at hand, then the upsides of parallelism go away

- Some processors might have easier tasks than others, or are more efficient than other nodes. So even if you have a bunch of people, the task moves as slow as the hardest subtask

- We want to evenly distribute the work amongst all processors

- However, a major bottleneck is communication speed

- Given the above, we want to write parallel programs that scale well

- Each piece can safely be done in parallel

- Keep all the processors busy

- Keep synchronization/ comms to minimum

Superscalar Processors

- A program is really just a series of instructions encoded in binary that a particular CPU can understand. The rate at which these instructions are executed is defined by the clock

- For simplicity, assume we have a CPU that executes exactly one instruction per cycle

- At it’s core then, CPU need to:

- Fetch/Decode: Figure out what instruction to execute

- Execute: Load the required data and do the thing

- Write Back: Update he internal state of the system

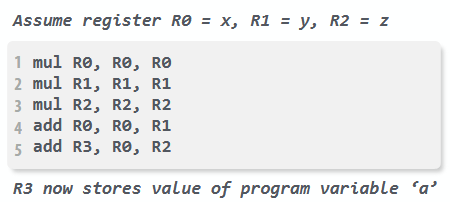

- Suppose that we have the program: $a = x^{2}+y^{2}+z^{2}$

- The above a the sequential version of the program

- What happens if you could execute two instructions at the same time? You could run $x^{2}$ and $y^{2}$ in parallel, then add them in parallel with doing the z multiplication, then add up the final results. So now it takes 3 clock cycles

- This is the idea behind instruction level parallelism (ILP)/ superscalar processors

- The key idea: some instructions can be run at the same time without interfering with each other. Hence, you can run multiple constructions at the same time!

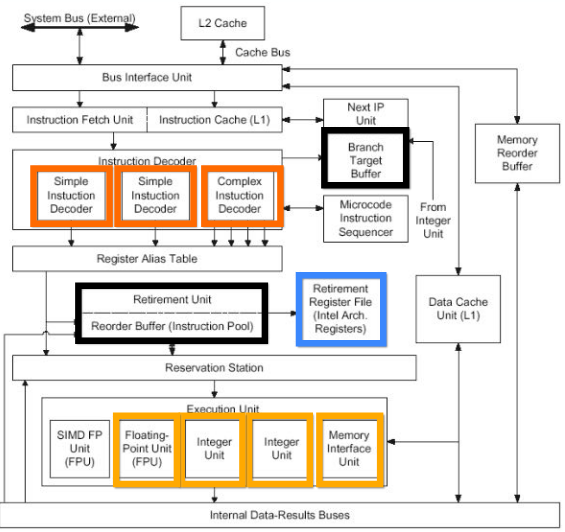

- A real world example: the Pentium 4

Single Thread Wall

- Unfortunately, the ILP gains seems to empirically saturate after 4 instructions

- In addition, there are hard power limits based on the frequency and voltages (EMI and all that)

- If chips get too hot, the don’t function anymore

- The way forward is multiple processors working in tandem

- Or alternatively, specialized processors for specific workloads

Memory

- There’s the old not-very-funny C joke: “The world is just a giant array of undifferentiated bits”

- In the programmer’s mental model, memory is exactly this

- Since most types of memory are not stored on the processor, you need to go fetch it from somewhere

- This takes a long time if you are getting this from the disk (Memory access times can be 100’s of cycles)

Caches

- Caches act as a way to help with these latencies: By providing an intermediate storage of highly accessed values, you reduce latency

- Caches should not alter the correctness of a program, only the performance

- Cache has two methods of “data locality”:

- Spatial locality: nearby addresses are more likely to be accessed (think array iteration)

- Temporal locality: high frequency addresses will more likely be accessed in the future

- Cache can have some hierarchy (L1,L2, L3)

- it could be implemented as DRAM (variable cycle count)

- but the important part is that whatever the caching system should be opaque (most) programmers

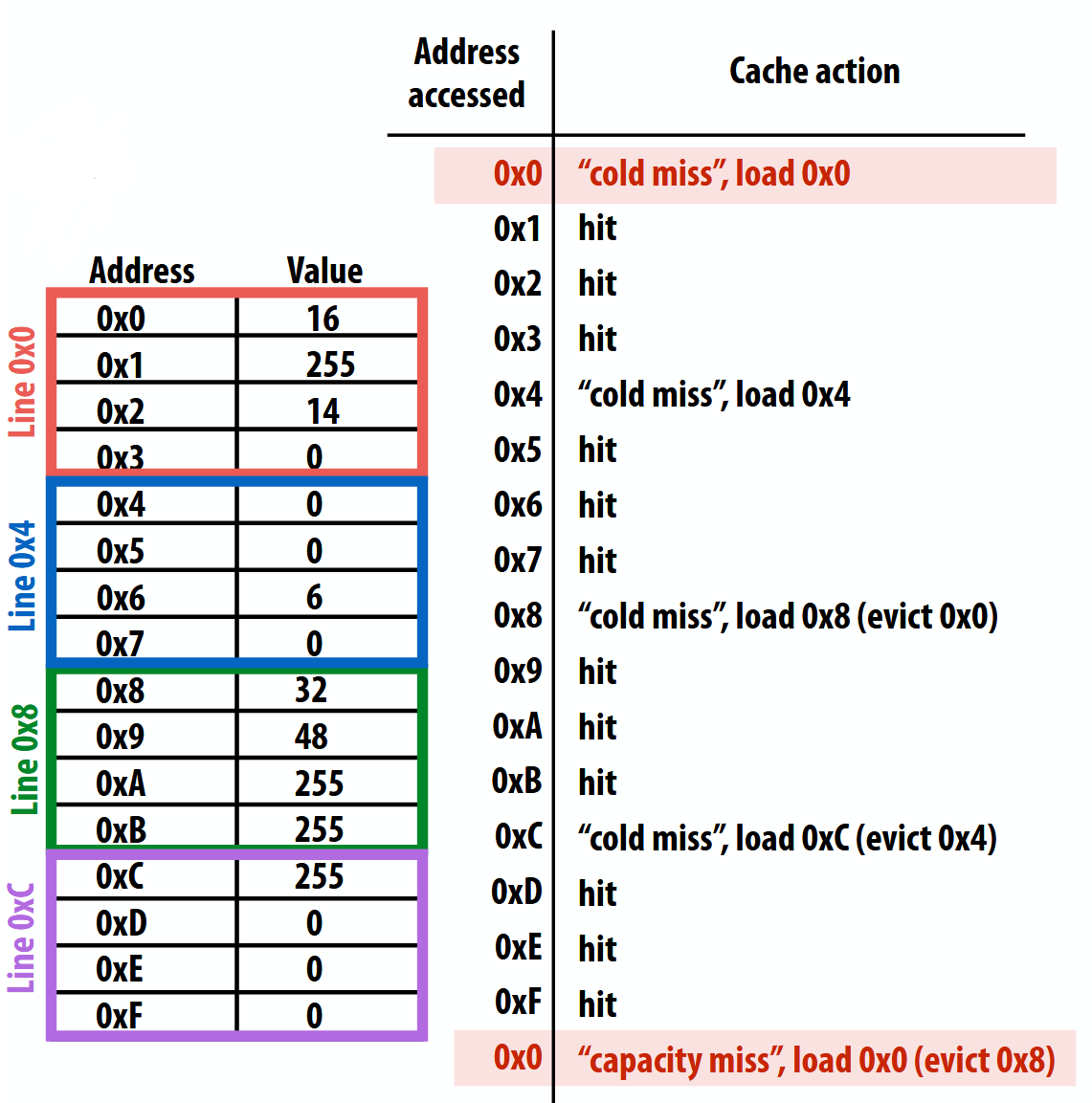

- The smallest unit of a cache is a “line” which has some width. If you get 1 address from memory, the adjacent memory values are put into a cache line. Subsequent memory addresses check the cache first before going to memory

- There are a bunch of policies for how the cache decides what data is high frequency. For now, just assume that a cache of size N bytes stores the last N addresses accessed

- New values follow LRU policy (least recently used) ie. the oldest access gets replaced first

- As a concrete example, say you iterate through addresses 0x0 and 0xF with a cache width of 8 bytes and a line width 4 bytes. The above shows the access pattern

- You get a cache miss every 4 bytes, and the least recently used cache address gets evicted if the cache is full

- Modern CPUs make predictions about what data will be fetched (so called “pre-fetching”). If the CPU guesses wrong, you can get reduced performance

Stalling

- Suppose that you miss the cache, and are now spending a very long time getting memory from DRAM/disk

- While you are waiting for the access, you can swap to a different program and do work there

- There might be a period where the first thread finished stalling and is in a runnable state, but is not being ran by the processor

- This is OK if aiming for a high throughput system. However, there is a “no free lunch theorem” trade off between throughput (ie. pipelining a bunch of work) and latency (ie. reducing the time each task takes )

- A CPU’s utilization rate is defined by the time spend doing actual work instead of stalling. This heavily depends on the number if instructions you can run before stalling.

- Adding more threads once you are at 100% utilization rate doesn’t increase the utilization. It just delays when you get back to the original task

Moving Past Single Core

- Since you hit a wall in single core performance, one way to increase performance is to use the transistors to make multiple cores instead of making the ILP logic properly

- Another way is to use SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data)

- You have one register with a bunch of bits in them (for concreteness, say 256 bits). You then subdivide each subsection of this large register (say 64 bit chunks). Each chunk then gets passed into their own ALU

- Hence the name: a single instruction can work on the multiple chunks of data in a register

- For SIMD, you need to ensure that each subsequent loop executes the same set of instructions across the same elements (called “coherent execution” or “instruction stream coherence”)

- Coherent execution is NOT a requirement for parallelism across multiple cores

- If a program lacks instruction stream coherence, it is called “divergent execution”

- On a GPU, you have N instances of a program running in parallel on a large number of different cores. Divergent execution in this context can cause massive performance hits

- SIMD can be expressed at the compiler level (via AVX2 instructions on intel for instance) or can be done implicitly by the hardware

Branches

- Remember that you are assuming that all iterations of the loop you are optimizing are independent of each other. How do you deal with conditional branches (re: if/else kind of statements)?

- Idea: Have all ALU cores try to run the if branch. If the condition is satisfied for that particular iteration, enable the computation, otherwise disable the ALU core. After that, repeat for the else branch, but disable the other set of registers

Latency Issues

- Think of driving down the highway. If you wanted to increase the throughput (ie. how many cars per hour can move along the highway), you need to either:

- Increase the speed of each car

- Increase the number of lanes

- Memory is the same. There is some maximum throughput/bandwidth which you can transfer data on a channel

- Memory Latency is defined as the time it takes to transfer any one item

- You can increase the throughput of a system while maintaining a fixed latency by pipelining your system (ie. when one subprocess finishes, immediately begin a new subprocess)

- This approach is latency limited: you can only go as fast as the slowest subprocess

- Incidentally, this is how multiplication takes “a single cycle”. This refers to instruction throughput, not latency

- Ie. it takes like 4 cycles to run a multiply instruction end to end, but only 1 cycle assuming proper pipelining

- To go to the extreme, this of a GPU. The max bandwidth is in the TB/sec. Transferring enough memory to saturate this bandwidth is physically impossible

- However, even a 1 percent utilization rate is still much faster than an 8 core CPU

- Modern computing therefore is constrained by the memory bandwidth!

- Performant programs fetch data from memory less often

- Doing more math instead of more memory requests can be beneficial to performance (up to a point)

Parallel Programming Idioms/ ISPC

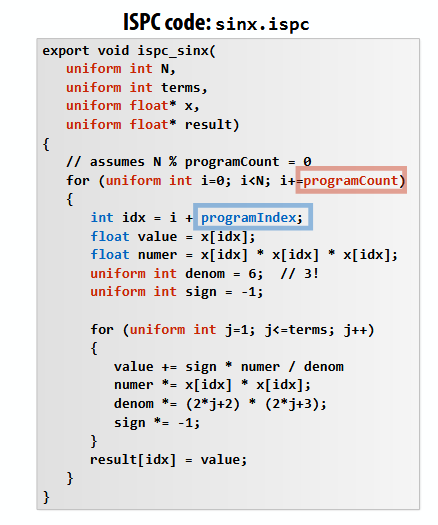

- ispc is the Intel SPMD Program Compiler which provides programming primitives

- Calling a ISPC function spawns a “gang” of ISPC program instances which run concurrently

- Each instance has it’s own copy of local variables Some keywords unique to ISPC:

- uniform: type modifier which asserts that all instances use the same value for this variable (non necesssary for correctness)

- programCount: the number of simultaneously executing instances in a gang (uniform value)

- programIndex: the id of the current instance in the gang

- foreach: a parallel loop keyword. This demands that work required to execute all of these loops be done by the gang as a whole, and not each instance

- It’s the compiler’s job to assign iterations to program instances in the gang

- There are a bunch of caveats where this will either be undefined or give a compiler error

- If multiple iterations of a loop body can write to the same memory location (race conditions are bad)

- Cannot return many copies of a variable which expects one return value

- cannot have a uniform value which gets assigned a different value across instances

- The above program interleaves the assignment of program instances (Ex: instance 0 works on indices 0, 8, 16 …)

- Temporally, at time t=0, each instance is working on a contiguous set of indices, so you can run a packed vector load

- You could also do “blocked” assignment, where each instance does a contiguous set of loop indices

- With this setup, you need to access disparate memory locations at t=0

- Requires “gather” instructions (vgatherdps) to implement (which can be costly SIMD)

- If you need to talk between instances, ISPC gives you some intrinsics:

uniform int64 reduce_add(int32 x);: compute sum of a variable across all program instances in a ganguniform int32 reduce_min(int32 a);: compute the min of all values in a gangint32 broadcast(int32 value, uniform int index);: Broadcast a value from one instance to all instances in a gangint32 rotate(int32 value, uniform int offset);: For all i, pass value from instance i to instance i+offset% programCount

- There is a difference between the semantics of an abstraction (ie. what should something do?) and the implementation (ie. how is something implemented)

- A great deal of caution should be made to disentangle an implementation from the semantics

- For ISPC, the abstraction is that the compiler spawns programCount logical instruction streams

- The implementation is the compiler emitting SIMD instructions with the appropriate masking

- There is some leakage with the uniform keyword (in that you need to think about if a value is shared across all instances)

- This abstraction/implementation is not unique!

- What if you didn’t want to provide fine-grain control of what happens in each instance? You would remove programIndex and programCount and be forced to use uniform outside the foreach loop

- You could also disallow array indexing and force the programmer too think about collections of data (think numpy!)